Introduction

Trigger warning: I have consulted for all companies that commercialize CART. If you cannot see past this, then this post is not for you.

The administration of novel immunotherapies that harness the power of T cells has revolutionized the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). The depth and durability of responses are far superior to those of previous approaches. Accordingly, the timing of introducing these therapies continues to move forward, with a possible future of them being integrated into frontline therapy. In 2025, one of the most pressing questions is whether CARTs should be employed at the time of the first relapse in MM. The question is of high relevance given that in April of 2024, the FDA approved the use of cilta-cel in patients with only one prior line of therapy. So, how do we go about making a decision?

There are diverse opinions regarding the optimal time to use CART, given the range of other treatment options available for patients. The views of MM experts are not unified, and arguments can be made for its use either later or earlier. Additional data from clinical trials will help her address some of these questions, but until then, patients will continue to face this decision in the foreseeable future.

Here, I propose a series of arguments that could be used to support the use of CART at the time of a first relapse. While I declare myself still pondering, I am very fast approaching the decision that CART should be considered and likely used in all suitable patients facing a first relapse, and here is why:

Outcomes and efficacy

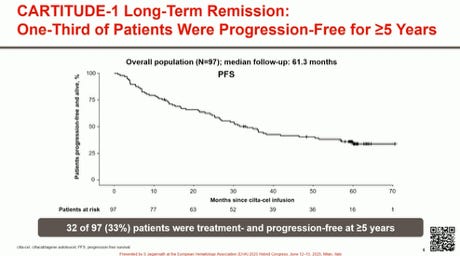

Efficacy results have so far been the greatest for CART (and arguably comparable to those of bispecifics) in the RR MM setting. Depth of response, MRD negativity, overall survival, and duration of clinical benefit surpass anything previously reported. Responses occur fast with rapid disease control. We have now seen that, in the setting of CARTITUDE-1, 30% of patients appear to be free from progression at 5 years, without any additional therapy.

Challenges remain, such as how to make these more durable and how to address certain subgroups (e.g., patients with extramedullary or bulky disease). However, these factors are prognostic features that identify patients who derive less benefit from CART versus patients in the same cohort who receive CART. However, when comparing CART with similar patients treated with other therapies, the results may still be superior.

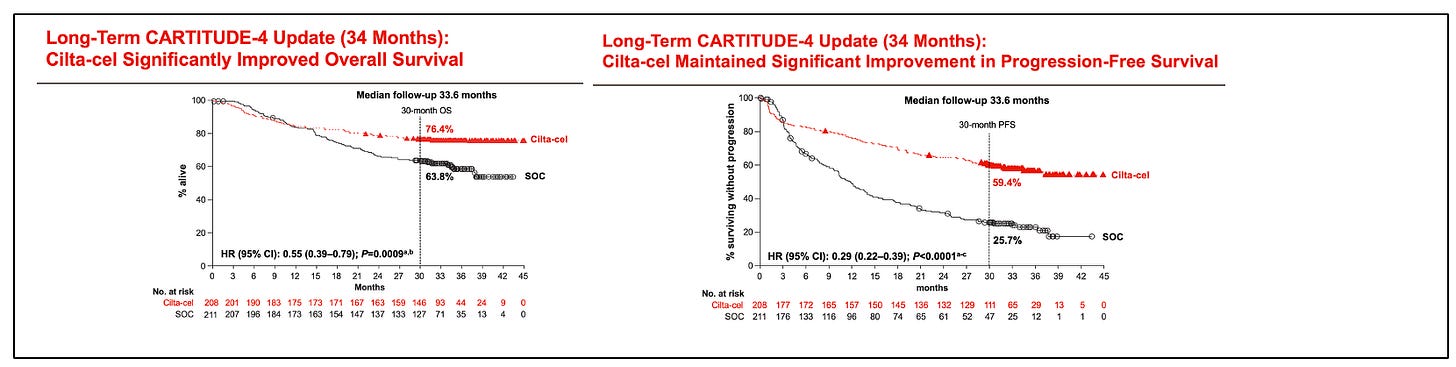

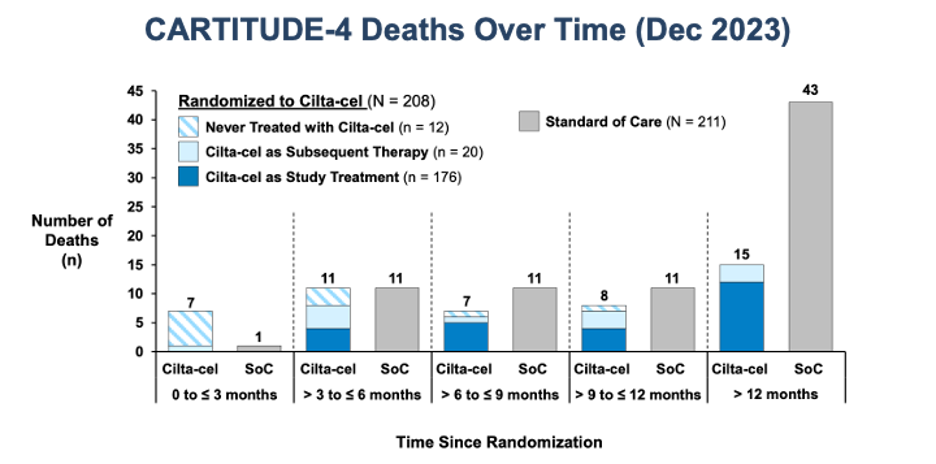

CARTITUDE-4 shows improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Interestingly, in the long-term outcomes report of CARTITUDE-1, the presence of high-risk or extramedullary disease was not prognostic in long-term responders (they were those with a higher tumor burden).

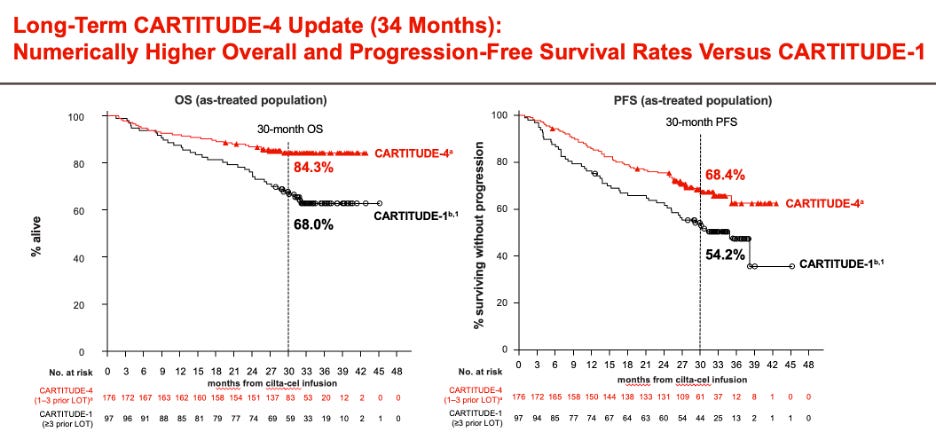

One of the most pressing questions is whether the clinical benefit of CART, regardless of when it is administered during the disease, is similar. A perception had lingered that efficacy outcomes are similar for CART used early versus later in the disease course. While aspirational (“we still have a great treatment for late relapses!”), it should have been clear from the beginning that this would not stand the test of time. First, it is predictable by clonal evolution that the more advanced a tumor, the less benefit patients will derive from any given therapy. Second, empirical data strongly suggest that earlier use is associated with more prolonged disease control, as evidenced by comparing outcomes of CARTITUDE-1 and CARTITUDE-4, and by evaluating PFS by lines of therapy in CARTITUDE-4.

Attrition

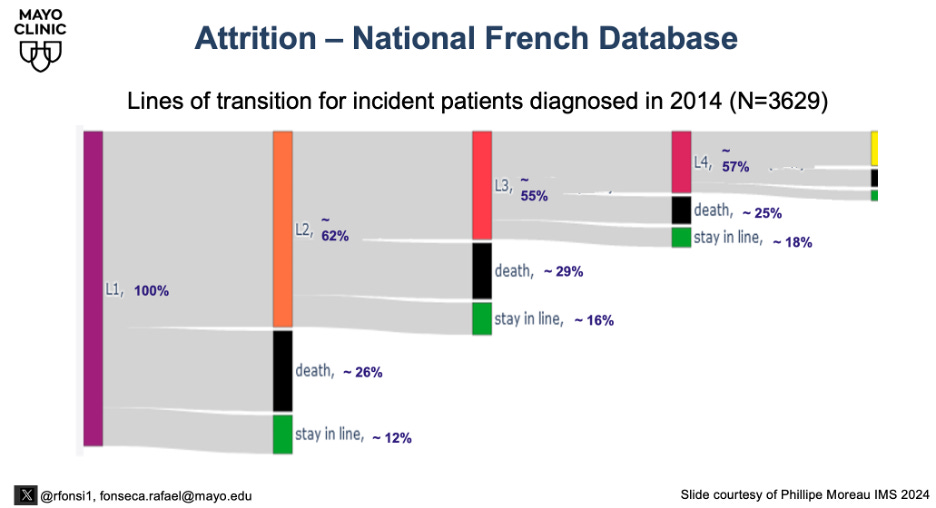

The concept of attrition is now well documented in the medical literature. Several studies show a meaningful portion of patients do not move on to the next line of therapy, many because of disease progression and death. Legitimate arguments can be had regarding the parameters used to define attrition, but the reality is that it should not be assumed that a future opportunity will exist to use any therapy. The sequencing of therapies matters at the individual level, and the risk of attrition needs to be considered when selecting therapies. Because of attrition, the best therapies should be used when it is more likely they can be used. The French national database now shows a rate of attrition consistent at about 25%. When comparing. A sequence strategy of A followed by B, or B followed by A, requires an intermediate discount due to attrition. This concept should temper the aspirational decision to save a CART “for later.”

Safety

The development of safe therapies is essential for success, and current reports show a significant risk of life-limiting and serious complications that can occur in the context of CART therapies. Some of these toxicities are indeed of considerable concern, such as the so-called motor-neuron toxicity (MNT), prolonged cytopenias, and possibly secondary malignancies. In a recent real-world evidence (RWE) publication, the risk of death not associated with relapse was estimated at around 10%. Given these considerations, one must carefully weigh trade-offs and ask us, “As opposed to what?”

Short-term toxicities

Myeloma experts are keen to better manage and prevent short-term toxicities such as CRS and ICANS. A more proactive approach has made the management of these more successful, and they pose a lesser risk to patients. In fact, an aggressive approach to managing CRS and ICANS may provide some protection against toxicities, such as MNT.

Motor neuron toxicity

MNT remains the most concerning of toxicities, and its incidence and preventive and treatment strategies need to be known with precision. A risk of 1% may be undesirable, but it is still likely to provide safety assurances. However, a long-term risk of 3 to 5% would be problematic. In CARTITUDE-4, the risk was estimated at less than 1%, but the RWE report showed 2%. MNT is unlikely to improve once it is clinically established in a patient, although anecdotal cases suggest that the use of high-dose cyclophosphamide may be beneficial.

Importantly, MNT appears to be more common in patients with more advanced disease, intense CRS and ICANS, advanced age, and those with a rapid rise in absolute lymphocyte counts. Although yet to be confirmed, using CARTs in patients with less tumor burden (e.g., at early evidence of a first relapse) may diminish the risk of delayed MNT. Additionally, early intervention with corticosteroids to prevent excessive initial expansion of CART may lessen the risk. Lastly, early intervention upon incipient symptoms (with IT or systemic chemotherapy) is now being proposed to halt any further neuronal damage and prevent more serious complications. The combination of selecting the right patient and implementing proper monitoring and intervention may alleviate the concern, even if it doesn’t eliminate it. Novel CART constructs that may have less risk of MNT are also being studied in large clinical trials.

Cytopenias, secondary malignancies, and other rare complications

The etiology of prolonged cytopenias remains unclear, and some patients continue to require growth factors and transfusions. The risk of secondary myeloid malignancies is also of concern, but it isn't easy to discern the contributions of CART versus prior exposure to other anti-myeloma agents.

I believe the risk of T-cell lymphomas is a minor one and does not significantly influence my decision-making process. In some patients, we have seen the emergence of colitis, which can be severe and lethal. These cases appear to involve localized T cell expansions in the gut, which can lead to chronic diarrhea and malabsorption.

Infections

Infections remain the major contributor to non-relapse mortality for CART patients. Careful attention to prevention strategies and early treatment of suspected infection is essential. Patients can develop infections due to B-cell dysfunction (hypogammaglobulinemia), neutropenia, bacterial infections, viral infections, and infections related to T-cell immunosuppression. The causes and recommendations have been covered in detail elsewhere.

Enterocolitis

Recent reports have revealed a rare complication arising in those with prior CART – an inflammatory enterocolitis (~2%). Patients can suffer profound diarrhea, malabsorption, and in some cases, it has been lethal. In some rare circumstances, an associated low-grade T-cell lymphoma has also been identified. While rare, this complication can be devastating to those affected.

Non-relapse mortality (NRM)

A recent RWE series of cilta-cel reported on an NRM of approximately 10%. This finding raised significant concern among MM investigators due to its implications for OS. It is worth considering that this number will be higher during the first few years of CART use and should be lower when people use these therapies in healthier patients with shorter durations of prior therapy. Additionally, a more proactive approach to the prevention and early treatment of infections can help mitigate this risk. It is worth remembering that patients undergoing CART in this RWE report are individuals who would normally have multiple other risks for mortality. Nevertheless, the risk of death not attributable to disease progression needs to be accounted for as we formulate decisions regarding next best treatment.

Timing of treatment

Employing CART later in the course of the disease exacerbates many of these potential risks as patients will have more burden of disease, greater exposure to other immunosuppressive MM therapies, depleted bone marrow reserves, and a greater risk of infection. In contrast, the use of CART for a first relapse could be done in such a way that planning will allow for patients to be treated without them having extensive disease, and often without the need for bridging therapy. With careful modern monitoring, the process of starting T-cell collection for CART manufacturing can be conducted early, such that the timeline minimizes MNT.

Anchoring bias – inertia and loss aversion

Part of the hesitancy in using CART earlier is based on anchoring, or historical bias. If, in 2025, we were routinely using CART and a new clinical trial reported a combination therapy as intriguing, and perhaps equally effective, but one that required weekly drug administration with significant time demands for patients, we would likely not recommend it. I believe there is a significant risk of bias towards the use of approaches with which we have familiarity, primarily because of the time when such options were developed.

The bias against the earlier use of CARTs is also based on what D. Kahneman calls System 1 thinking. In his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” he highlights the extra weight humans place on the aversion of negative outcomes (“loss aversion”). The net results of using CART, despite the risks of MNT, infections, and mortality, are outperformed by the improvements in overall survival demonstrated. Despite these risks, you are more likely to live longer if you get a CART than if you don’t. The loss aversion effect is such that many individuals who read the medical literature with stringency and demand proof of overall survival before implementing new treatments are now hesitant to recommend CARTs in early relapses (first included) because of the loss aversion of toxicities.

Reason for pause?

A more cautious approach would suggest that additional information is needed to fully evaluate the risk of long-term complications, particularly concerning MNT. As additional information arises from RWE databases and clinical trials, we will have a better understanding of the magnitude of these risks. These risks will be context-dependent (e.g., prior treatment lines, disease burden), as well as dose-dependent and dependent on other treatment details. A GPRC5D CART was reported to have great efficacy against RR MM. However, in an NEJM paper, when patients were treated at high doses, cerebellar toxicity was observed with serious consequences. All T cell therapies should be considered as being the proverbial double-edged sword. If the target is present elsewhere to elicit “On-Target, Off-Tumor” effect, toxicities may arise.

Is there ever a situation where an alternative treatment to CART would seem preferable?

If a patient experiences a relapse long after they have stopped therapy, and if the patient is likely not resistant to IMIDs, a combination of daratumumab plus pomalidomide may be an effective and attractive alternative. Alternatively, a patient with a t(11;14) would seem like a good candidate for a combination of daratumumab, venetoclax, and dexamethasone. However, one must recognize that these treatments not only require repeated administration (with logistic and toxicity consequences), but that they are usually only temporary (palliative). Lastly, if a patient is deemed not to be a CART candidate for any reason, a bispecific may be of benefit. No other self-evident options come to mind

Conclusion

A cogent argument can be made for CARTs to be used for the first relapse.

As of now, that means cilta-cel only, but other products will be introduced to the market.

If additional information confirms the lack of MNT in patients treated with anito-cel, a novel BCMA CART, then the safety margin will widen in favor of earlier use of CART products.

Given these considerations, including a high degree of efficacy, the safety implications, treatment convenience, and the risk of loss by attrition, and if one can overcome a historic bias

Dr Fonseca, as always, I love reading your posts. I am very glad that cilta-cel is available for first relapse, and there are many patients for whom I believe the benefits clearly outweigh the risks. I will offer five key respectful rebuttals to some of your points above though. All in the spirit of good debate and discussion.

1. Is the 30% progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years a mirage or reality? Historically, these results from clinical trials have not translated well to real-world data. The MAIA trial of dara/len/dex in newly diagnosed myeloma is a stark reminder—a PFS exceeding 5 years in the clinical trial but only 2-3 years in the real world. Censoring, progression adjudication in trials, patient selection bias, focusing only on intent-to-treat analysis and many other reasons make me think that we are extremely unlikely to see 30% PFS at 5 years in the real world, and to quote this to patients is setting up wrong expectations. I do think that a certain minority (10%, 15%?) will benefit to this exceptional degree, and that in itself is a reason to celebrate for such a heavily pre-treated population.

2. I respect greatly your work on attrition. However, the fundamental argument that undercuts attrition with respect to CAR-T comes from two key observations. In newly diagnosed myeloma trials, PFS1 has often not correlated well with OS, likely because patients can go on to get good treatments in the future. If attrition = death or immense morbidity, we would at least see PFS1 correlate with OS. Talking specifically about CAR-T, the randomized trial for ide-cel (KarMMa-3) showed no overall survival benefit despite a compelling PFS benefit because they allowed for crossover, and the patients in the control arm got ide-cel later. As a result, one way of interpreting the study from an overall survival perspective is that early ide-cel = later ide-cel. We cannot make such conclusions about cilta-cel, because unfairly Janssen did not allow crossover in their study. Nevertheless, the attrition argument is severely weakened given that many patients in the control arm of KarMMa-3 went on to receive CAR-T and ultimately achieve comparable overall survival.

3. The toxicity of cilta-cel is probably worse than we think it is, in part because we are just now recognizing toxicities and paying more attention, and these toxicities may not have been noticed earlier. The real-world study that you quoted with a 2% Parkinson's rate also showed other toxicities including cranial nerve palsy in 11 patients (5%), diplopia in 4 (2%), posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in 2, dysautonomia in 1 patient, and polyneuropathy in 1 patient. Furthermore, neurological toxicity may not be completely averted by giving in an earlier line—it sure appears that T-cell expansion is robust in patients that are less heavily pre-treated!, and neurological toxicities have been seen even in less heavily pre-treated cohorts of patients (https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper201783.html)

4. Many patients I see in clinic today may choose to defer a toxic CAR-T product today, with the hope of a safer (but still effective) CAR-T product in the future. This remains to be seen and perhaps is wishful thinking, but I do think a safer CAR-T product in the future will change the paradigm and lead to broader acceptance.

5. Many patients relapse today who are sensitive to both daratumumab and lenalidomide. Long-term data from the POLLUX trial (median PFS 44.5 months) is very reassuring, and toxicity is much more predictable than cilta-cel. Such a group of patients very clearly may benefit more from a simpler and safer regimen, even if it does require much more treatment compared to a one-and-done CAR-T. On a side note, the one-and-done nature of CAR-T can be debated given ongoing care needed afterwards, such as infection prophylaxis, managing of blood counts, etc.

So overall, I am very thankful to have CAR-T available at first relapse. There are many patients who are clearly great candidates for it, and there are many patients who after a thorough discussion of risks/benefits wish to proceed. I am all for them having access to it. However, as discussed above there are many reasons to be cautious with universally recommending it at first relapse.

And lastly—thank you for sharing your thoughts and respectfully allowing me to share mine. I remain a great fan of all you do, and look up to you as an inspiration.

Manni